Displacement, Cervical Intervertebral Disc Without Myelopathy

Displacement of a cervical intervertebral disc refers to protrusion or herniation of the disc between two adjacent bones (vertebrae) of the cervical spine in the neck (vertebrae C2 through C7). Note that there is no disc between the skull and C1 or between C1 and C2. Although displacement is commonly referred to as a slipped disc, the disc does not actually slip.

The discs between each vertebra form a cushion that absorbs shock and allows movement of the neck. The discs are composed of an inner gel-like material (nucleus pulposus) and an outer ring of tough, fibrous material (annulus fibrosis). Sometimes the fibrous material develops a weak area that allows the nucleus pulposus to intrude into the spinal canal (disc displacement or herniation). Depending on the site of the intrusion, the disc may compress either the spinal cord or the exiting nerves, or both. Pressure on an exiting cervical nerve root where it exits the spinal canal can cause changes in sensory (touch, pinprick, temperature), motor (muscle strength), and reflex function in the innervated areas (upper limb). These types of changes are collectively referred to as

radiculopathy; however, disc displacement may also occur without radiculopathy. Cervical radiculopathy also may be caused by

tumors,

infection, or vertebral

fracture. Disruption of the annulus fibrosis itself may also cause symptoms (annular disruption, distension, or tear). This can allow the nucleus pulposus to leak out of the disc, causing an intense and painful chemical inflammation (radiculitis).

Disc herniations (commonly called “soft discs” in the neck) tend to occur in younger adults who have only mild loss of disc height (disc degeneration) and thus have enough disc material still present to produce a protrusion or herniation. The same radiculopathy symptoms and signs on exam can be produced without a disc herniation in older individuals who no longer have enough disc height (disc material) to produce a herniation, but rather have arthritic spurs (osteophytes) as the structure that pinches the nerve root. In these older individuals the term used to indicate the cause of the radiculopathy is “hard disc,” meaning bone spur or “bony bar.”

Causation and Known Risk Factors There are no prospective cohort studies to assess causation of cervical disc herniation. There are case-control studies that pose the question of whether smoking, heavy lifting, and being a professional driver increase the risk of developing a cervical disc herniation.

Diagnosis

History: Important items to note in the history include: information about pain (onset, location, quantity, quality, setting, aggravating and alleviating factors, associated symptoms), percentage of pain that is axial (neck) vs. peripheral (upper limb) pain, and history of neck injury. Disc-related pain without nerve root involvement may be vague and diffuse. Radicular pain from nerve root compression typically follows a dermatomal pattern in upper limb; neck pain may be paradoxically absent. The pain may have begun with no apparent cause, or there may be a history of injury to the neck. Some episodes begin during or shortly after the person does a “low violence” activity that the individual has done many times before, and this “minor trauma” may be blamed for the event by both health care providers and patients. The location of the pain, sensory loss, and muscle weakness in the limb usually allow the physician to determine which nerve root is most likely to be compressed by a disc herniation.

These individuals sometimes rest the symptomatic upper extremity on the top of their head to decrease pain. Coughing or sneezing makes the pain worse, and affected individuals may report that they are more comfortable sleeping in a reclining chair than in a bed. If treatment is not sought, individuals may notice increasing weakness in the affected limb. A history of prior or existing systemic illness should be obtained, including chronic disease (e.g., diabetes, heart disease, atherosclerosis, nervous system disorders, arthritis, infections, malignancies, or weight loss).

Physical exam: Cervical intervertebral disc displacement usually limits range of motion of the neck. The exam may show that neck movement aggravates pain, particularly when bending the head backward (hyperextension) and turning the head from side to side (rotation). The manual application of cervical compression and distraction during the physical exam may help to differentiate between disc pain and pain from other causes. Pain may increase when downward pressure is applied to the top of the head (cervical compression test) and may be relieved by

traction (cervical distraction test). Examination should include assessment of muscle strength and changes in sensation and reflexes in the upper extremities. Lower extremities may be examined to rule out signs of myelopathy.

Tests: Laboratory blood tests are usually not necessary, but may include erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) to evaluate inflammation, white blood count analysis to rule out infection, rheumatoid factor, thyroid and parathyroid studies, and liver function studies. Human leukocyte antigens may be typed. Results of these tests help rule out other conditions.

Imaging studies show the extent of degenerative changes, but do not give any information about function. Plain

x-rays show narrowing of the disc space and bone spur (osteophyte) formation, if present, as well as possible metastatic disease, spinal deformity, and spine stability. If mechanical instability is suspected as a cause of recurrent pain, it can be documented by x-rays taken with the neck bent forward (flexion) and bent backward (hyperextension).

MRI or

myelography combined with

CT are considered the best ways to diagnose a herniated cervical disc. Electromyography (

EMG) may distinguish nerve root compression from a peripheral nerve problem such as

carpal tunnel syndrome or

ulnar nerve entrapment. Nevertheless, a normal EMG does not rule out nerve root compression. As in the lumbar spine, asymptomatic herniations are frequently seen in normal volunteers. For this reason, disc herniations on imaging studies must correlate with the clinical signs of nerve root deficit observed on physical examination.

Treatment Conservative therapy is the first line of treatment except in cases of severe or progressive neurologic compression that is usually in a specific area of skin supplied by a specific spinal nerve (dermatome) and can be matched to an MRI with disc protrusion at the same level. Bed rest is rarely indicated. Intermittent traction may be applied, and the individual may be taught to use intermittent traction at home.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may be given to relieve pain and decrease inflammation. Either oral or injected corticosteroids (“cortisone”) are commonly prescribed if there is severe radicular arm pain. If pain is severe, a narcotic may be added; in some cases, an antidepressant or an anticonvulsant may be used for its analgesic effect. If

anxiety and tension are prominent, sedatives may be helpful. Muscle relaxants are frequently prescribed; however, their effectiveness probably is due to their sedative action. Narcotics, sedatives, and muscle relaxants are ideally used only for brief periods. Ongoing use should be weighed against the potential for addiction or abuse. Other treatments such as ice, heat, massage, and

ultrasound therapy may help relieve pain.

As symptoms subside, activity is gradually increased and includes

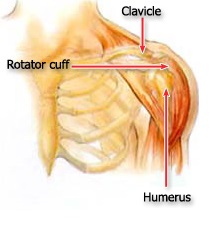

physical therapy to strengthen and mobilize the muscles of the neck and shoulder. An independent home exercise program is an essential component of any physical therapy. Good posture and frequent changes in position may help prevent fatigue and decrease pain. Preventive and maintenance measures, such as exercise, stress management, and proper body mechanics, should be continued indefinitely. If there is no improvement during the first 2 weeks, or if pain is still disabling after 6 weeks, further evaluation is necessary.

Most cases of cervical disc displacement with or without radiculopathy can be managed conservatively.

Pain Interventional procedures are within the scope of conservative treatments for disc related pain withor without Radiculopathy( neck pain radiating to the arm with numbness and/or tingling sensations in the arm). These include mainly Cervical Epidural Injections done under Flourospcopic Guidance (live X-ray) where medication (corticosteroid) is delivered directly to the area of the inflamed disc or nerve noot.

However, surgery is indicated in cases where (1) pain management has failed, and the individual has intractable upper limb pain with imaging evidence of a correlating nerve root compression; (2) there is mechanical instability of the spine associated with disc herniation; (3) signs of neurological deficits are increasing (e.g., progressive or severe muscle weakness or severe arm pain with objective signs of nerve root compression on imaging); or (4) the disc herniation is massive and compresses the spinal cord, causing bowel and/or bladder control impairment, lower extremity weakness, sensory loss, or gait disturbance.

Surgery involves removal of the protruding nucleus pulposus (

discectomy). The traditional method for removal of the disc is open discectomy under general anesthesia. The discectomy is most often done through an anterior approach (incision in the front of the neck), and is most often accompanied by a simultaneous fusion, frequently supplemented by use of a plate and screws. An alternative that is occasionally chosen is posterior (back of the neck incision) discectomy in which a portion of the vertebra that acts as a roof (lamina) over the spinal nerve is removed, creating a small window into the spine. The surgeon then removes the herniated disc material through this opening.

An alternative for younger patients who do not have facet arthritis or other significant aging change is anterior discectomy with simultaneous artificial disc replacement. This procedure appears to give early results as good as anterior cervical discectomy and fusion, but long term results are not yet known or published (Gebremariam).

Rehabilitation The primary focus of rehabilitation for a cervical intervertebral disc displacement without myelopathy is to decrease symptoms and increase function. Although exercise may be uncomfortable initially, individuals must be instructed in the benefits of ongoing exercise in managing the symptoms.

The first goal is to decrease symptoms, primarily pain. In combination with pharmacological management, modalities such as heat and cold can be used. Immobilization with a soft collar is rarely indicated; however with significant soft tissue pain, it might be necessary for a very short period of time (up to 3 days). While managing pain, individuals can be instructed in gentle exercises (Boyce). Due to the variability in response, the treating practitioner must pay careful attention to tolerance to treatment. Initial exercises may include isometrics, stretching and/or gentle range of motion. Spinal manual therapy may reduce symptoms when combined with active treatment. Postural training should be initiated as soon as tolerated by the individual.

Once symptoms subside and range of motion is restored, the individual should progress to strengthening and stabilization exercises of the neck, shoulders and upper trunk (Ylinen). Limited treatment with cervical traction has been shown to be beneficial for neck pain when done in conjunction with exercises, although traction must be carefully administered to avoid adverse response.

The individual should also be instructed in a home exercise program to complement the supervised rehabilitation, and trained to care for and protect the neck from recurrence of symptoms. An ergonomic evaluation can prove helpful in avoiding or modifying activities and work positions that may aggravate the symptoms.

Psychotherapy may be indicated to support the individual and identify associated factors that may contribute to the symptoms. A short course of cognitive pain management may be beneficial for individuals experiencing psychological distress or lack of improvement with treatment (Klaber Moffett).

Complications Worsening of the condition (enlargement or increasing size of the disc herniation) may cause pressure on the spinal cord as well as on additional nerve roots. Functional disturbances and/or pathological changes in the spinal cord (myelopathy) may occur as a result of the displaced disc pressing on the spinal cord.

Muscular atrophy and sensory disorders may occur as the result of nerve root compression.

Source:

http://www.mdguidelines.com/displacement-cervical-intervertebral-disc-without-myelopathy